The Deep Green Reading List

I have started a movement: the Deep Green Right. This is a movement that takes seriously inegalitarianism, the necessity of the state and authority, and rejects the tired twentieth-century dichotomy of state versus market. We are not interested in implausible global solutions to the human predicament, nor do we place our hopes in planetary governance. We take deep ecology seriously. We recognise that energy is the basis of wealth, and that the economy and society must be understood through a biophysical lens. Evolution, ecology, thermodynamics, physics, political theory, and cognitive science are all integral to understanding the structure of our predicament. We are evolved beings, naturally inclined to organise into groups. These groups coalesced into states, which competed, and in so doing created cultural evolutionary pressures favouring large-scale cooperation, softer religions, and the rise of philosophy. War bred innovation. Famine, disease, and disaster incentivised automation, and we lurched toward our technified modernity occasionally punctuated by great explosions of violence.

This modernity, though explosive and disorienting, also gave us the heat engine, and led to breakthroughs in medicine and mortality. We surged beyond the natural checks that had previously hemmed in population and consumption. This created a delusional sense of unbounded optimism—a false abundance we continue to exploit. We built systems of finance and debt reliant on perpetual exponential growth, even as they degrade the ecosystems that make our lives possible. We extract more than nature can replenish and do so at an accelerated rate. The twenty-first century is not uncertain—it is profoundly predictable. Do not be misled by techno-optimists. This is an age of great unravelling. It is time for the harsh gods to return, for the politics of necessity to replace the politics of desire, and for us to take real measures to ensure the prolonged survival of ourselves and the flourishing of life and beauty on this green-blue Earth.

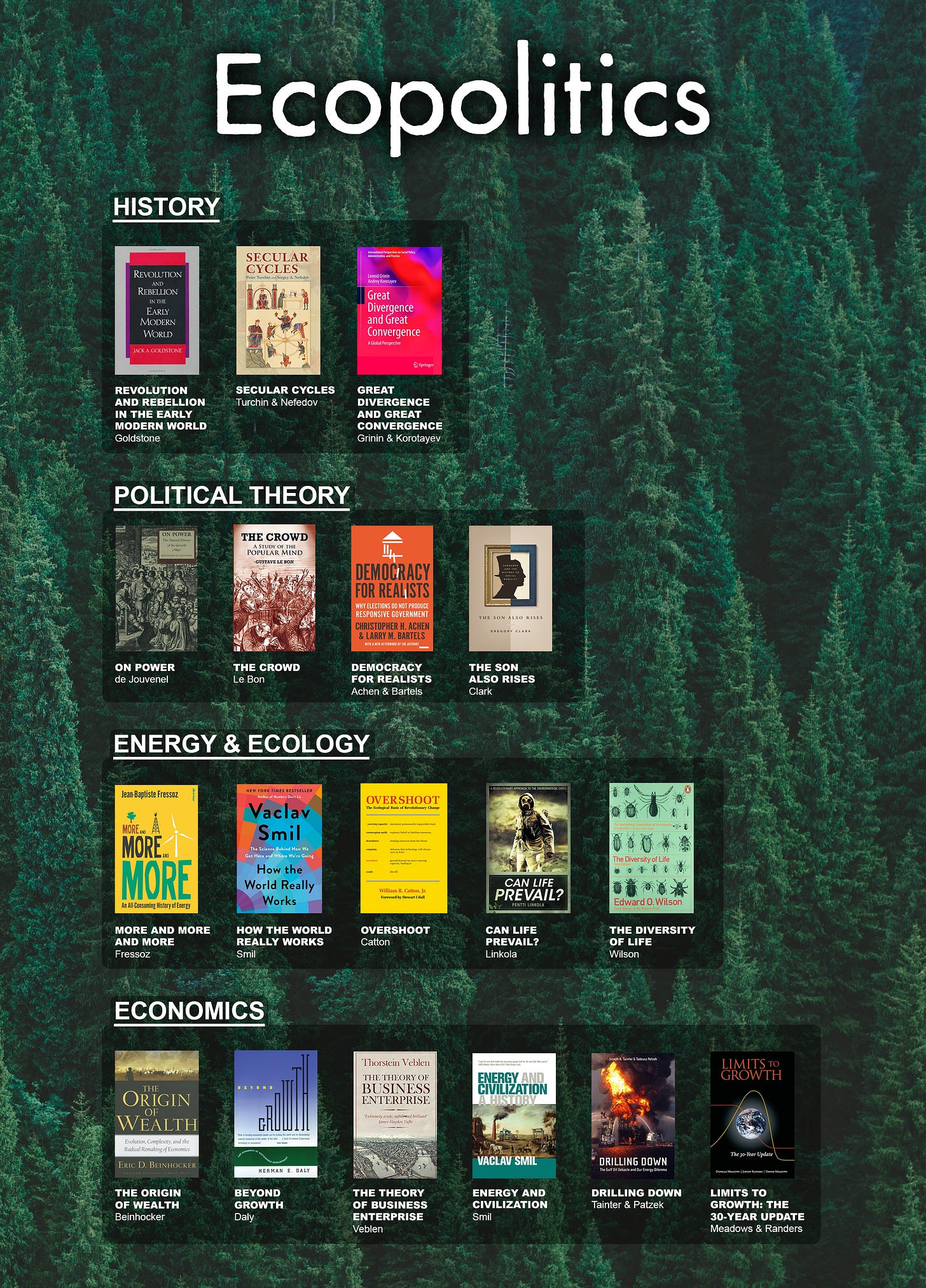

This post provides a reading list for any interested in this new movement and the intellectual basis upon which it is drawn and the giants upon whose shoulders it rests. I divide the list into several sections, here is an infographic made by a friend:

History

I. Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World – Jack A. Goldstone

This might seem like an esoteric way to start the list, given its cumbersome and specialist-seeming title, but Revolution and Rebellion in the Early Modern World provides a powerful toolkit for understanding political revolution. Goldstone presents a compelling model known as structural-demographic theory, which is as relevant today as it was in the historical systems he analyses. The core insight is the long-term influence of demographic trends on political structures, explaining the recurring, near-simultaneous collapses across different Eurasian societies.

It’s a structural theory in that it focuses on the relatively invariant anatomy of the premodern state: elites, taxation systems, and the mass population. Goldstone shows how demographic pressures—particularly population growth—drive inflation, which then destabilises societies by simultaneously undermining elite recruitment, immiserating the masses, and weakening the state’s fiscal foundations. He carefully traces these trends, refuting alternative explanations, and in doing so offers a kind of night vision for navigating the complex history of the entire agrarian age. Many of the same structural pressures exist today of course.

II. Secular Cycles – Peter Turchin and Sergey Nefedov

Peter Turchin significantly expanded upon Goldstone’s structural-demographic model by incorporating more mathematical modelling and integrating it with the framework of cultural evolution. Cultural evolution applies the logic of natural selection to societies as complex adaptive systems, and has been increasingly used to make sense of developments in culture, economics, history, and political theory. It incorporates concepts like group selection and explores how evolutionary pressures for large-scale cooperation and competition have shaped the direction of history—whether towards larger states, bigger firms, or social norms like monogamy. For instance, polygynous societies often suffer from internal disloyalty and fragmentation, which puts them at a disadvantage compared to monogamous ones at scale.

While many of Turchin’s works explore cultural evolution more directly, Secular Cycles focuses on the expansion and refinement of Goldstone’s demographic-political model. It introduces the crucial concept of elite overproduction and examines recurring long-term social cycles across different historical contexts—extending the theory both backwards and forwards in time, backwards to the Roman Empire and forward to the Russian revolution. This book deepens and systematises the structural-demographic theory, strengthening its explanatory power and setting the stage for more culturally focused analyses that will appear later on this list.

III. The Great Divergence and Convergence: A Global Perspective – Leonid Grinin and Andrey Korotayev

This book builds further on the structural-demographic and cultural evolutionary perspectives by placing the dynamics of global inequality, technological divergence, and eventual partial convergence into a deeply historical and systemic framework. Grinin and Korotayev analyse the origins of the so-called “Great Divergence”—the dramatic lead taken by Western Europe during the early modern and industrial periods—and trace how various civilisational zones responded over time. What makes their approach invaluable is its synthesis of economic history, world-systems theory, and mathematical modelling. Like Turchin and Goldstone, they take demographic and structural factors seriously but extend the scope to analyse how global interdependence, catch-up growth, and technological diffusion have led to a new phase: the Great Convergence. Their work helps contextualise the current multipolar world and provides tools for understanding both global inequality and systemic transition from a longue durée perspective.

Political Theory

IV. On Power – Bertrand de Jouvenel

One of the key things to understand about modernity is the rise of the state, a process that stretches back thousands of years. While the agrarian period was marked by cyclical collapse due to Malthusian constraints, the long arc of history reveals a slow and relentless growth of state capacity, particularly accelerated by technological advancement. Jouvenel provides an excellent starting point for grasping this dynamic. He introduces the “High–Low versus Middle” model, in which Power seeks to augment itself by undermining intermediary elites—turning to the masses, stirring their fury, and bypassing traditional power centres.

Jouvenel traces the steady rise of the state’s ability to mobilise resources and highlights its conflictual relationship with the dominant economic class. Societies are complex systems not just of cooperation but also of sabotage and tension. Where Goldstone and Turchin emphasise intraelite conflict, and Marxists focus on class suppression from above, Jouvenel reveals the intrinsic tension between surplus-extracting dominant classes and a surplus-extracting state with its own security logic. The state, locked in the permanent threat of war, must centralise and expand its reach, often clashing with the very elites it depends on. Marxist style class conflict are abundant in history, especially since medium-scale agrarianism of kings and nobles. crushing the peasants when things go wrong, but Jouvenel’s framework adds a crucial dimension: the recurring and irreducible rivalry between elites and the state itself.

V. The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind – Gustave Le Bon

Elite theory has provided a fundamentally accurate framework for understanding political and social organisation: elite institutions shape public opinion, the masses are largely apathetic, the iron law of oligarchy holds firm, and there is often little connection between truth and what the masses believe or desire. However, one major failure of classical elite theory was its widespread prediction of the inevitable demise of mass democracy. Far from disappearing, mass democracy not only endured but entrenched itself more deeply into the political fabric of the modern world—a question that will be addressed later in this list. But even if elite theory stumbled here, The Crowd by Gustave Le Bon remains a masterpiece of early sociology, and no one has more vividly, forcefully, and memorably diagnosed the behaviour of mass psychology.

Le Bon captures the irrationality, emotional volatility, suggestibility, and conformity of crowds with chilling precision. He describes how individuals, when absorbed into crowds, lose their sense of self, moral restraint, and capacity for critical thought—becoming easily led by symbolism, repetition, and authority. His insights help explain the rise of mass movements, the emotional tenor of modern politics, and the terrifying speed with which rational discourse can collapse under collective pressure. Though written in the late 19th century, The Crowd remains strikingly relevant. It offers a key to understanding the modern age’s paradox: a society governed by democratic ideals in theory, but increasingly shaped by the unconscious, primal forces of mass behaviour in practice.

VII. Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government – Christopher H. Achen and Larry M. Bartels

Achen and Bartels provide perhaps the most important modern update to the sociological insights of Gustave Le Bon. Where Le Bon diagnosed the irrationality and volatility of mass behaviour in general, Democracy for Realists brings this critique into the heart of modern liberal democracies. The book delivers a crushing, evidence-based dismantling of the folk theories of democracy—those comforting myths in which informed, rational citizens deliberate, weigh evidence, and vote in accordance with their interests and values. Instead, Achen and Bartels draw from decades of political science, especially the Michigan school tradition and the foundational work of Philip Converse, to show that political behaviour is driven far more by identity, partisanship, and deep-seated loyalties than by policy preferences or issue-based reasoning.

The public, far from being a collection of rational actors, is mostly inattentive, ideologically incoherent, and highly susceptible to symbolic cues. Voters routinely punish or reward governments for things wildly outside their control—natural disasters, shark attacks, or economic crashes which have little to do with policy—demonstrating the persistence of primitive, associative modes of political cognition. Elections, they argue, do not work as mechanisms for retrospective accountability or prospective choice in any meaningful sense. Instead, partisanship functions as a social identity, shaping perception itself. This work gives empirical teeth to the pessimism of Le Bon, filtered through rigorous data and statistical modelling, and represents a paradigm shift in how political behaviour is understood. It is indispensable for grasping why mass democracy endures, not because it is rational or effective, but because it offers low stakes rituals and blind tribal ways to express disaffection which don’t tear apart society.

VIII. The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility – Gregory Clark

The Matthew Effect—the tendency for advantage to accumulate and entrench itself—is a core destabilising force in complex societies. Korotayev, Grinin, Turchin, and Goldstone all trace how inequality and elite overproduction erode state stability over time. Interestingly, Goldstone also observed that increased social mobility—what might be called rising social entropy—can be just as destabilising. Chronic inflation, rapidly shifting asset classes, and the fragmentation of estates led to the collapse of established elite lineages, while others shot up through opportunism and speculation. The result was a breakdown of the social hierarchy’s coherence and the rise of civil conflict. But Clark offers a bracing corrective from the right: in reality, social mobility is much lower than modern liberal myths would have us believe. The social order is surprisingly persistent across generations, even across different economic systems, religions, and cultural structures.

In The Son Also Rises, Clark uses an ingenious method—tracking surnames across centuries—to reveal that elite status tends to persist far beyond what standard mobility measures capture. He shows that underlying this persistence is not merely wealth or institutional advantage, but something more heritable: what he calls “social competence,” which is plausibly genetic in part. This places a massive empirical weight behind elite theory. His work undermines the notion that policies aimed at equalising outcomes can significantly shift mobility rates. While Clark does not deny ethical arguments for reducing inequality—for reasons of dignity, fairness, or political stability—he makes it clear that such efforts should not be confused with efforts to radically alter the transmission of status. Mobility and inequality are separate axes, and confusing them leads to misguided policy and false hope. This is a book that closes the door on liberal optimism about meritocracy while strengthening the structural realism that runs through this whole list.

Energy and Ecology

IX. More and More and More: An All-Consuming History of Energy – Jean-Baptiste Fressoz

This fantastic recent book by Jean-Baptiste Fressoz exposes the delusion behind the idea of an energy transition by highlighting the additive nature of modern energy systems—each new energy source is layered on top of the old, rather than replacing it. But the book goes far beyond this basic insight, offering a deep analysis of the logistical entanglements between energy and raw materials, leading to an exponential expansion of everything—a dynamic Fressoz terms energy symbiosis. From whale oil to the supposed “replacement” of wood with coal, and the relatively unknown but critical interdependence between oil and coal, the book is filled with vivid examples showing the increasing scale and complexity of material and energy throughput. Instances where older materials genuinely disappear are shown to be extremely rare exceptions, not a rule of technological development.

Fressoz also traces the strange and largely ideological genealogy of the notion of an energy transition, and is relentlessly sharp in his critique of techno-optimist narratives surrounding climate change and ecological crisis. These narratives often ignore Jevons Paradox and the real material history of energy systems, relying instead on abstractions and wishful thinking. Linear history is taken apart, along with the comforting myths of mono-materialist stages in civilisational development. This book is essential reading for anyone seeking to grasp the real depth of the predicament we face. It equips the reader with conceptual tools to understand why dreams of dematerialisation falter—and why the material logic of modernity remains stubbornly unbroken.

X. How the World Really Works: The Science Behind How We Got Here and Where We’re Going – Vaclav Smil

Vaclav Smil’s How the World Really Works is a sober and empirically grounded dismantling of the myths surrounding modern civilisation’s supposed break from material and energetic constraints. At its heart is a biophysical understanding of the economy—Smil draws our attention to the inescapable dependence of civilisation on exosomatic energy, energy used outside the human body to perform labour and sustain systems far beyond our biological limits. He offers a precise and accessible breakdown of the fossil fuel basis of modern agriculture, detailing how natural gas is essential to fertiliser production, how diesel powers mechanised farming, and how every calorie we eat is saturated with fossil carbon. His treatment of water and land use also lays bare the scale of artificial input required to sustain billions of people, inputs only made possible by dense, portable, and energy-rich fuels.

Smil identifies four key material pillars of modern civilisation: ammonia, cement, steel, and plastics. Each is fundamentally dependent on fossil fuels, not merely for energy input, but for their very chemical composition. He emphasises the importance of volumetric energy density in explaining why hydrocarbons remain so dominant: energy-dense, easily transportable, and embedded in nearly every aspect of industrial and post-industrial life. Petrochemicals, far from being marginal, saturate everything from food production and packaging to medicine and electronics. Smil is not a polemicist but his work is quietly devastating. It forces readers to confront the scale of the task involved in any serious decarbonisation effort and to grasp how deeply fossil carbon is entwined with the material sinews of modernity.

XI. Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change – William R. Catton Jr.

William Catton’s Overshoot is one of the foundational texts for understanding the ecological and energetic limits of industrial civilisation. At the heart of the book is the concept of overshoot—the condition in which a species, through technological expansion and temporary abundance, exceeds the long-term carrying capacity of its environment. Catton introduces the notion of ghost acreage to describe how industrial societies appear to sustain themselves not by drawing solely on their local ecosystems, but by importing resources, food, and energy from across the globe—or by relying on fossil fuels, which represent the drawdown of millions of years of stored sunlight. This temporary abundance has allowed us to delay ecological feedbacks, but only by stealing from the future. Modern industrial society is cost-efficient but energy-inefficient: it can reduce financial costs in the short term while catastrophically increasing ecological costs over the long term, thus creating a deeply unstable metabolic structure for civilisation.

Beyond ecological diagnostics, Catton offers a sharp cultural analysis of American society during what he calls the age of exuberance—a period defined by rapid growth, expansionist ideology, and the unquestioned assumption that more is always possible. He frames this as a kind of cultural intoxication, a product of historically unique circumstances rooted in colonisation, fossil fuel abundance, and technological acceleration. As the limits begin to bite—through environmental degradation, resource depletion, and systemic instability—this exuberance is beginning to give way to anxiety and denial. The concept of overshoot, in this light, becomes not just an ecological reality but a moral and temporal one: it is theft from the future, a pillaging of the earth’s regenerative capacities in service of a brief and unsustainable burst of complexity and comfort. Catton’s work remains prescient, uncompromising and essential for anyone trying to understand the predicament of the 21st century.

XII. Can Life Prevail? A Revolutionary Approach to the Environmental Crisis – Pentti Linkola

Pentti Linkola’s Can Life Prevail? is a ferociously unflinching collection of ecological essays that rejects the comforts of liberal environmentalism and confronts the modern crisis with rare moral clarity. Central to Linkola’s thought is the idea that modernity has undergone a shift from a politics of necessity—where survival dictated limits, discipline, and restraint—to a politics of desire, in which consumption, individualism, and growth are treated as non-negotiable rights. This shift has led to the construction of what he calls ecologically impossible objects: material artefacts and systems (from skyscrapers to global air travel) that could only ever exist under extreme energy abundance and are utterly incompatible with ecological sanity. In poetic and visceral language, Linkola captures what William Catton diagnosed technically as overshoot, turning it into an aesthetic and civilisational indictment.

What makes Linkola’s work particularly notable—and controversial—is that he recognises no easy or democratic path out of the ecological abyss. He saw clearly that the scale of the problem demanded both authoritarian discipline and radical localism, rejecting the liberal belief that mass participation and voluntary restraint would be sufficient. Though deeply rooted in his native Finland, with richly observed writing on forests, wildlife, and rural life, Can Life Prevail? transcends its national context. It contains a treasury of sharply argued and often beautifully written essays on everything from technology and education to city life and ethics. Linkola remains a marginalised figure in mainstream discourse, but for those willing to engage with uncomfortable truths, his work serves as a necessary counterpoint to the prevailing environmental narratives of green growth and democratic optimism.

XIII. The Diversity of Life – Edward O. Wilson (1992)

E.O. Wilson’s The Diversity of Life is a sweeping and passionate account of the biological richness of the planet and the intricate evolutionary processes that produced it. As one of the 20th century’s leading biologists and the father of sociobiology, Wilson offers not only a scientific overview of biodiversity but also a philosophical and moral argument for its preservation. He makes clear that life on Earth is not just a catalogue of species, but a vast, interdependent web of relationships—a biocomplexity that is both staggeringly intricate and finely balanced. Wilson explains the evolutionary origins of this complexity, the ecological roles of diverse organisms, and the cascading consequences that result from species loss. His vivid descriptions of ecosystems and their interwoven functions offer a powerful reminder that the biosphere is not a backdrop to human history, but its living foundation.

This book belongs on the list because it articulates what is at stake in the era of ecological overshoot and collapse: not simply the human project, but the unraveling of Earth’s evolved order. Biodiversity is not an optional aesthetic feature of life, it is the result of billions of years of adaptive complexity, and its erosion is a civilisational death knell.

Economics

XIV. The Origin of Wealth: Evolution, Complexity, and the Radical Remaking of Economics – Eric D. Beinhocker

Eric Beinhocker’s The Origin of Wealth offers a powerful and much-needed reframing of economics through the lens of complexity theory and evolutionary dynamics. Rejecting the static, equilibrium-based models of neoclassical economics, Beinhocker argues that economies are better understood as complex adaptive systems—ever-evolving, path-dependent, and driven by the accumulation of useful knowledge. Drawing from evolutionary biology, computer science, and systems theory, he describes economic progress not as efficient allocation but as a dynamic process of innovation, recombination, and selection across networks of agents. This approach restores a sense of realism and historical depth to economic thinking, making it compatible with ecological and energetic constraints.

The book earns its place on this list because it helps bridge the gap between cultural evolution, biophysical economics, and the material realities described by thinkers like Turchin, Smil, and Fressoz. Beinhocker’s emphasis on bottom-up emergence, the role of entropy in production systems, and the non-linear pathways of development provides conceptual tools to understand how economic complexity both arises and collapses. While more optimistic in tone than others on this list, The Origin of Wealth is indispensable for anyone trying to grasp how wealth, innovation, and structure emerge not from equilibrium, but from dynamic evolutionary pressures embedded in a thermodynamic world.

XV. Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development – Herman E. Daly

Herman Daly’s Beyond Growth is a foundational text in ecological economics, offering one of the most direct and coherent challenges to the assumptions of mainstream neoclassical economics. His core move is conceptually simple but devastatingly powerful: he places the economy within the wider biophysical system of the Earth, rather than treating it as a self-contained, abstracted machine. Once this change is made—treating the economy as a subsystem of the finite ecosphere—virtually every classical assumption about infinite growth, substitutability, and externalities begins to break down. Daly shows that economic activity is fundamentally entropic, drawing down low-entropy resources from the environment and returning high-entropy waste. The supposed circularity of economic models becomes impossible to defend when confronted with the laws of thermodynamics and the limits of ecological regeneration.

Daly’s work is not only conceptually airtight—it is also pragmatic and policy-oriented. He argues that growth, in the physical sense, is no longer economic beyond a certain point and that the obsession with GDP masks a deeper structural irrationality. Beyond Growth introduces key concepts like a steady-state economy, throughput limits, and the necessity of biophysical accounting—all of which are grounded in the physical realities that economists have long ignored. While neoclassical models rely on idealised, frictionless systems, Daly’s ecological framing brings us back to Earth, both literally and theoretically. This book is essential for understanding why our economic orthodoxy is ecologically incoherent, and how a shift in conceptual framing, simple, indisputable, and rooted in physical law can transform the entire discipline.

XVI. The Theory of the Business Enterprise – Thorstein Veblen

Thorstein Veblen’s The Theory of the Business Enterprise offers a biting and still-relevant critique of the capitalist economy by distinguishing sharply between industry and business. Industry, in Veblen’s view, is the realm of productive labour—of engineers, scientists, and workers whose aim is to meet material needs through applied knowledge. Business, by contrast, is not primarily interested in production but in pecuniary gain—profit maximisation, market control, and financial manipulation. Veblen shows how the logic of business often sabotages the potential of industry: production is held back to maintain scarcity, competition is crushed to ensure rents, and technological progress is slowed or distorted by vested interests. In short, the institutions of capitalism often obstruct the very efficiencies they claim to promote.

This makes Veblen essential for understanding how capital accumulation functions as a parasitic force within modern economies, one that generates systemic inefficiencies and periodic crises, not because of accidental mismanagement, but because of the structural misalignment between productive potential and financial incentives. Veblen prefigures many later critiques of rentier capitalism, financialisation, and institutional inertia, but what makes his analysis especially prescient is his grasp of capitalism as an evolutionary and cultural system, full of irrational habits and symbolic performances. His insights resonate today in an age where shareholder value often trumps material functionality, and where business elites manipulate uncertainty to profit while real-world infrastructure and ecological integrity decline. Veblen helps us see that the economy is not a neutral or rational system, but a site of ongoing conflict between competing logics—and that the logic of business is increasingly misaligned with survival.

XVII. Energy and Civilization: A History – Vaclav Smil

In Energy and Civilization, Vaclav Smil traces the long arc of human history through the lens of energy conversion, showing that every major transformation in society—from foraging to farming to industrial civilisation—has been driven by changes in how we access, convert, and use energy. Central to the book is the idea that society functions like a metabolism: it requires constant energy input to maintain structure, perform work, and support complexity. The increasing efficiency of energy use—particularly in converting stored energy into mechanical work was fundamental to the rise of modernity. Smil meticulously shows how these gains in energy density, reliability, and scale underpin everything from transport and agriculture to communication and computation.

The book offers a sweeping yet detailed account of the energy foundations of human systems, covering animal muscle, wind and water, biomass, fossil fuels, and electricity. Smil shows that while innovation has greatly improved our ability to harness energy, it has also led to ever-increasing consumption, not substitution or dematerialisation. Energy, he insists, is not just one sector among many—it is the precondition for all economic, political, and social activity. Energy and Civilization makes clear that without understanding energy history, we cannot understand civilisation itself—and that any future trajectory must reckon with the biophysical realities that have always governed our species, whether we recognised them or not.

XVIII. Drilling Down: The Gulf Oil Debacle and Our Energy Dilemma – Tadeusz W. Patzek & Joseph A. Tainter

In Drilling Down, Tainter and Patzek bring together two crucial dimensions of the modern world—energy and complexity—to show how deeply entangled they are, and how this entanglement is driving us toward diminishing returns. The book begins with a detailed analysis of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, not as a technical failure, but as a symptom of an increasingly fragile system. In order to maintain current levels of production, we are forced to extract energy from more difficult, dangerous, and complex environments, requiring ever-greater investments of capital, technical knowledge, and risk management—what the authors call the energy-complexity spiral. The deeper point is that civilisation doesn’t energy; it consumes net energy, the amount of energy left over after the energetic cost of extraction (EROI). As EROI declines, societies must spend more energy and effort just to maintain their basic functions. This has lead to a secular trend of increasing amount of people and capital in the energy sector since the late nineties, cancelling out the effects of automation and energy efficiency which had decreased work in the energy sector up until that point.

This leads to a dynamic of escalating complexity and falling returns. Tainter, famous for his theory of societal collapse as a result of complexity overshoot, shows here that our very solutions—more oversight, more technological layers, more infrastructure—create new problems and higher energetic overhead. Patzek contributes his deep understanding of thermodynamics and petroleum systems to demonstrate just how far we are from a post-fossil world. The result is a sobering, systemic view of modernity as energetically precarious, structurally brittle, and locked into a treadmill where solving today’s problems worsens tomorrow’s. This book is essential for grasping not only the limits of fossil fuel extraction, but the deeper logic of collapse baked into high-energy, high-complexity civilisations, or at the very least those based on growth.

XIX. Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update – Donella Meadows, Jørgen Randers, Dennis Meadows

This landmark systems analysis synthesises many of the core themes running through this list—energy dependence, resource depletion, overshoot, environmental degradation, and exponential growth—into a single, dynamic model of planetary limits. The 30-year update refines the original 1972 Limits to Growth study with more robust data and highlights how little progress has been made in altering civilisation’s collision course with biophysical constraints. It demonstrates that without fundamental structural change, humanity is heading toward a convergence of crises, driven by a growth-based economic model embedded in finite ecological systems. The book also underscores the reality that technological optimism, without corresponding social and political transformation, is insufficient to prevent systemic breakdown. In bringing together thermodynamics, ecology, economics, and feedback dynamics, Limits to Growth serves as both a warning and a framework for understanding the 21st-century predicament in deeply interlinked, planetary terms.

Interesting list of books! I'd throw out a few that might interest you.

Human Scale Revisited by Kirkpatrick Scale

Small is Still Beautiful: Economics as if Families Mattered - Joseph Pearce

Technopoly - Neil Postman

Dark Age America - John Michael Greer

Was surprised not to see anything by Jacques Ellul on this list as well.

Curious to see your future writings as to what should be done both at the individual, but also nation-state level.

I suspect de-growth is an infeasible sell to broader society until some form of collapse hits. Given that, seems like the goal as an individual would be to…

a) Get rich now

b) Transition that wealth into ownership & control of key resources

c) Manage this portfolio to maximize wealth with future growth, but also prep for any collapse

Become lord of timber, oil, and mining, but also hedge your bets for collapse.